***

We all love a character with a unique set of armour: the baresark Rek from David Gemmell’s Legend with his enchanted armour of bronze, or Tomas from Raymond Feist’s Riftwar Cycle with his gleaming white armour which gifted him incredible power. Although such armour exists, unfortunately, in fantasy worlds, it’s important to understand how things work in the real world, even at a basic level. This guide will, hopefully, arm you with what you need to enrich your tales.

The development of medieval armour kicked off during the Hundred Years War between the English and the French. English archers were butchering the French with arrow storms, wiping out their cavalry in particular. The French had to do something, and so an arms race ensued. Weapons were built to defeat armour, and armour built to withstand weapons. A vicious cycle with vicious motives.

Let’s have a look at a few types of armour.

Chain mail

Mail was one of the first types of metal armour developed, arguably by the Celts, though other sources say its origins came from Eastern Europe.

A coat of mail was a complex web of metal rings, each locked with an iron rivet. Such coats were made from brass or iron, though steel was deemed best due to its toughness.

A jacket or coat of mail was usually worn with a hood, or coif, of the same material to protect the head and neck.

As time marched on, small plates of leather or iron were added to the mail to protect key areas, such as the vital organs.

Mail was particularly effective against glancing blows. In battle, you are trying to strike a moving target, so mail was sufficient as most blows were glancing ones. Clean, powerful strikes were needed to disable a foe wearing mail. Blunt weapons were effective, causing haemorrhaging and concussion, so padded garments known as a doublet or gambeson were worn underneath to provide added protection.

Mail was lightweight and flexible. Good for the mobile knight. It was pretty easy to make, though laborious, and easy to repair. Another benefit to chain mail, a point which can slip the mind of writers, is that it was cheap and efficient, able to accommodate different sized warriors, unlike expensive plated armour, to which we now turn.

Plated armour

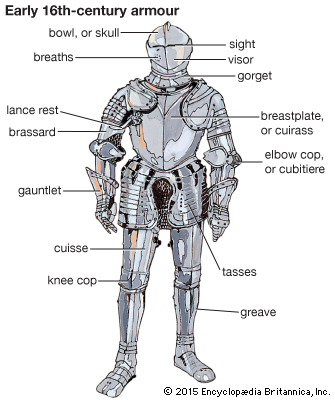

Most picture the knight when we talk about plated armour—rigid tin men that can withstand all manner of blows. Something like this:

As you can see, a knight’s armour is made up of a lot of different pieces. It took a while to get ready, with the help of somebody else needed, usually squires, who began with the feet and worked up from there.

Both doublets and chain mail were worn in conjunction with plated armour for that added protection, particularly for areas plate could not cover, such as arms and the groin.

Coats of plated armour soon came about, which consisted of a series of plates linked on top of one another. They could withstand high velocity strikes from a javelin or lance, driven home by somebody charging forwards on horseback. Only the most powerful strikes could pierce such armour. They looked something like this:

One of the main defensive strengths of plated armour came from its curved design, which deflected both blades and arrows. As with mail, steel was the best material due to its hardness, which was obtained by heating the steel to extreme temperatures and then submerging it into cold water, a process known as ‘quenching’. You may have seen steel workers doing this after forging the likes of blades and horse shoes.

Once quenched, the steel was re-heated to make it more resilient. Heating to the perfect temperature was key. In pre-thermometer times this was difficult as you can imagine, so instead, armourers observed the colour of the heated steel. When heated, steel turns from yellow, to brown, to blue, to red. Once blue, it is quenched a second time, permanently fixing its hardness. Arrows will bounce off steel crafted in such a way—unless from close range, as we discussed last week.

Wearing a suit of armour was like being in your own private world. The senses were deadened: sight limited, sound muffled, breathing stifled (depending on the type of helmet). It would have been extremely warm too. But it provided an odd sense of security. Fully geared up, you were a walking fortress.

With all that armour, it’s often assumed the medieval knight was immobile. Not quite. Each suit of armour was tailored to the individual. The aim was not to cause any impediment to movement. A warrior had to fight the enemy, and to fight his armour as well would be too distracting. The pieces of armour around the vital organs—the chest and head—were thicker and heavier than those on the arms and legs to try and reduce weight as much as possible.

Armour therefore wasn’t that heavy—a suit of armour weighed approximately 50 pounds, which is around 3 to 4 stone. If a knight fell from a horse, he could quite easily pick himself up, not stuck on the ground like a tortoise knocked on its shell.

This video provides an interesting perspective on a knight’s movement.

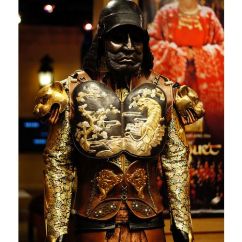

The appearance of armour was a big deal for knights. Chest plates had grand etchings. Pauldrons, gauntlets, and even leg armour were fashioned into elaborate designs. Here’s a few images. Share your favourites in the comments below!

Helmets

Helmets were arguably the most distinctive feature of an armoured knight. Some had pointed snouts, the purpose of which was to deflect arrows when walking into arrow storms. The eye slits were narrow to prevent all sizes of arrowheads from finding their way through. Vision in such helmets was extremely limited, but this was the cost of added protection.

The front part of helmets, or the visors, were there to raise or open so the wearer could breathe during taxing hand to hand combat, or scan around the battlefield.

Some helmets had chain attached which hung around and protected the neck, called an aventail, and most were padded inside, for added comfort. Who doesn’t like being comfortable when killing?

As with body armour, great efforts were made with the designs of helmets. Here’s a few different types:

Other types of armour

We mentioned gambesons above. These were worn on their own by those wanting greater speed and flexibility, but also by those unable to afford stronger armour. The padded material could absorb blows from blunt weapons and provided some protection from cuts, but against well forged weapons they were useless.

Another type of cheap armour, one up from gambesons, was boiled leather, also known as cuir bouilli. Strips of leather were boiled in water, though some sources record oil and wax being used, and even animal urine. Reeking of piss on the battlefield was another weapon in the arsenal I suppose. Leather could be stitched into coats, or added to mail to provide added protection.

Here’s a video showing the effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) of leather armour against arrows. Excuse the ‘on hold’ background music.

And let’s not forget the trusty steed. As knights became fully armoured, so did their mounts. Some wore a trapper – a covering of full chain mail—and down the line, some horses even had their own plated armour. Expensive indeed, and heavy—stronger horses had to be bred to handle the weight.

Resources

Here’s a superb glossary, with pictures, of all types of armour.

And if you want more, this documentary is excellent:

Leave a Reply